The Hardest Part: Nick Mamatas on Love is the Law

← Pictures: 2013 Local Author Holiday Book ExpoClay and Susan Griffith's "Tribute: Nelson Mandela" comic to be released this week →

The Hardest Part: Nick Mamatas on Love is the Law

Posted on 2013-12-11 at 12:00 by montsamu

Nick Mamatas is no stranger to writing whatever he wants, damn the torpedoes. And as Mamatas writes here about his latest novel — the Trotskyist/Crowley/Long Island noir Love is the Law — for “The Hardest Part”, writing can be the easy part. “If there was any difficulty in writing the novel at all, it was in writing the book so that it could end up in a bookstore somewhere.”

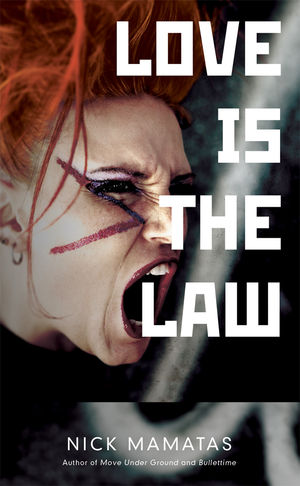

[caption id="" align=“alignnone” width=“185”] Love is the Law

Love is the Law

by Nick Mamatas

Dark Horse, October 2013[/caption]

THE HARDEST PART: Love is the Law

By Nick Mamatas:

Actually, writing Love is the Law was pretty easy.

I’m not the kind of writer, or reader, who falls for the well-worn trick of a single-sentence paragraph, but there you go. It was a breeze.

It was a breeze.

The idea came to me as a joke, when my then-agent asked if I had any ideas for a YA novel. (The YA “boy book” by a male writer is every agent’s recipe for a million-dollar payday.) I said, “Harriet the Spy, but a punk rocker and Trotskyist who is also really into Crowley.” I thought I was so darn clever that I tweeted the description, and my then-editor at Dark Horse Books said that she’d love to read something like that. So I went downstairs to my computer, wrote the first 1000 words—save typos, they are the first 1000 words of the book—and sent them over to her. By the end of the afternoon, and after a few encouraging emails, I was 2500 words in. The whole novel—inspired as it is by the tight noir writing of Goodis—is only 55,000 words.

Perhaps it should have been hard to write. The protagonist, a young woman named Dawn, has different genitals than I do. She knows how to drive. I don’t. Her father is a crack addict and her mother dead. My parents are fine. She’s the proverbial seeker who is born every minute. (Hey, isn’t it supposed to be sucker? Same difference.) I’m reactively skeptical, which is just as bad in its own way.

There are some commonalities though. We both have a grandmother suffering from dementia. She lives in my hometown—in the apartment my great-uncle George used to live in. When she peeps into the basement bedroom of her high school acquaintance Greg, the house is my cousin’s house, and the basement room the little set-up my uncle had in my grandmother’s home. We listen to the same radio stations, circa 1989. The older Greek woman she encounters is my late great-aunt Argyro. Dawn is me, even though our lives only intersect in the way that the lives of two neighbors who are strangers might.

Love is the Law is a fairly straightforward crime novel, as narrated by an individual who believes, deeply, in the power of magick, and also in the truth of historical materialism. Contradictory, you say? Of course, but personalities are born from the management of contradictions. Contradictions make character. So that was easy too. If you’re a writer and struggle with character, here’s a tip: create a character based on a strong cardinal trait of some sort, and then somewhere in the story have him or her act in opposition to that trait. Behold, the instant illusion of depth!

A crime novel featuring an unreliable narrator is hardly all that unusual. There’s even an Agatha Christie novel where the narrating sleuth committed the crime, as it turns out. Indeed, an unreliable narrator makes a crime story even easier to write—so long as you keep the reader believing in the character. A first person narrator is the shortcut to that belief. Human beings are very familiar with being told stories that begin, “The other day, I…”

If there was any difficulty in writing the novel at all, it was in writing the book so that it could end up in a bookstore somewhere. Love is the Law might look like urban fantasy at first, but most readers of that genre would be extremely disappointed in Dawn—a “strong female character” who is essentially a sociopath—and the sort of noir the book actually is hasn’t been widely published in years. Both mystery and fantasy are dominated by the series novel, and a series implies adventure. Love is the Law is a single slim volume, and an anti-adventure. Dawn cannot even bring herself to leave Long Island.

If anything, the book is a metaphysical or visionary novel, along the lines of The Alchemist. But in The Alchemist we’re told, “when you really want something to happen, the whole universe conspires so that your wish comes true.” In Love is the Law the lesson is that the universe is in a conspiracy against you, and your wish for absolute freedom. Worse still, the conspiracy is the one you really want to be true after all. A visionary novel with that theme is an all but impossible sell. Indeed, when I was Dawn’s age, I wanted nothing more than to be an obscure underground cult author, working in tawdry genres and playing philosophical games in prose that few people would care about. And lo, the universe did indeed conspire against me to make me exactly that, even as my literary agent was trying to guide me toward a million-dollar payday. As ever, I was free to write whatever I wished. I just had to get it into stores.

So I put in a gun and a fair amount of cocksucking.

The Hugo-nominated editor of Haikasoru, an imprint of VIZ Media which brings Japanese science fiction and fantasy to “America and beyond”, Nick Mamatas’ first full-length novel, Move Under Ground, was nominated for both the Bram Stoker Award and the International Horror Guild Award for Best First Novel in 2005. His recent anthologies, The Future is Japanese, co-edited with Masumi Washington, and the Bram Stoker Award winning Haunted Legends, co-edited with Ellen Datlow, have been critically well received.

Love is the Law is out in print and ebook from Dark Horse. In his NPR review, The AV Club’s Jason Heller writes: “A suburban fantasy in the tradition of grand urban fantasists like Emma Bull and Elizabeth Hand, the book rings profanely and profoundly. And it does so in a blitzkrieg of tightly riffed prose. When it hits a fever pitch of paranoia and postmodern ideology-mashing, it’s Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum boiled down to a minute-and-a-half hardcore song.”

Mamatas is a frequent contributor to Bull Spec, from fiction (“O, Harvard Square!” in issue #4) to multiple reviews (of Welcome to the Greenhouse in issue #5, of Zazen in issue #6, of Cory Doctorow’s The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow and Context in issue #7) to even kicking off “The Hardest Part” a little over a year ago when writing about his previous novel, Bullettime.